Stone, literature, landscape

for the UNSW Forum series, Friday 5 August 2005

My work begins with drawing, but cutting letters and images in slate and sandstone is now at the heart of it. But lettercutting is a complex medium, because there are many roles to fulfil. The first most obvious one is memorial maker, making contemporary, hand-made, expressive memorials. ‘Do you do gravestones?’ Well, yes. Then there are all the other genres: menhirs, garden furniture, fountains, commemorative installations, indoor artworks -- I actually have many hats.

The longest and most intimate conversations are those creating memorials, which in their specialised way are cultural objects in landscape garden settings. Recent works for Springwood, Waverley and Albion Park cemeteries and the little cemetery at Bungwahl near Smith's Lake have involved negotiations with the clients and with the municipal authorities.

My large slate dining tables, often 1.2 m × 2.5 m, carry perimeter texts, so that everyone seated has some fragment of poetry. Monumental slate benches such as the Robert Frost bench in the Orange Botanical Gardens can mark a specific location, in this case a path dividing in a wood.

Figure 1. 'Two roads', text by Robert Frost, Mintaro slate, collection Orange Botanical Gardens

Menhirs, or standing stones, carry text, and can suggest the European megaliths. These stones often seem to have intrinsic power, mass and form alone demanding respect and speaking to other landscape elements.

I make many tree plaques, texts and tree images, which can be hung as necklaces on trees, sometimes with a plasticised bicycle cable to the tree is not harmed.

Figure 2. No sky larking, Mintaro slate

Figure 3. Snows of yesteryear, Mintaro slate

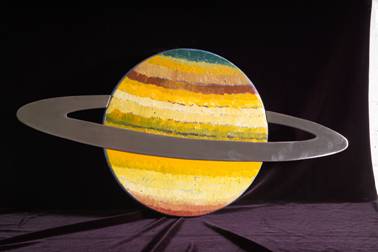

A set of slate discs became a solar system (these can be seen in the foyer of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music) using white and yellow gold, oil paints and gold size. Individually, moons and planets can look spectacular in garden settings, particularly as the twilight fades.

Figure 4. Moon, Mintaro slate, white gold

Figure 5. Saturn, Mintaro slate, oil paints, stainless steel

Great slate discs, up to 2 metres is diameter, can be inscribed and set in the ground, or used as water table fountains.

Invention, recombinations of materials, applying techniques from other disciplines and adventurous reading are all necessary for this work.

Each work or commission can be different in its process, but the conversation has a common aim: to respond to family needs, a place, or a poetic idea, and make an expressive form.

It is like the visual artist’s usual technique: to sit down, immerse yourself in a place, and by drawing reach an understanding of what you are seeing. This work involves similar patient attempts at understanding. Like drawing, it should be experiential. Often I will make a link between a landscape and place, and a poetic or literary fragment, hours or days after I have made a visit.

One illustration of this kind of source material in our environment are the journals, the great resource created by travellers and explorers, from Cook and the published journals of the early settlement through to Sturt, Mitchell, and Giles.

First, here, through language, is the experience of first glimpse of landscape and people, with all that is implied. Then there are names heard from Aboriginal people, recorded and applied to landscape and names bestowed. (Our part of the world is thick with references to the Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal, given by Mitchell.) The natural world is described by Europeans with enlightenment values; and moments of huge significance to the people concerned are described.

By way of illustration I will describe two such moments.

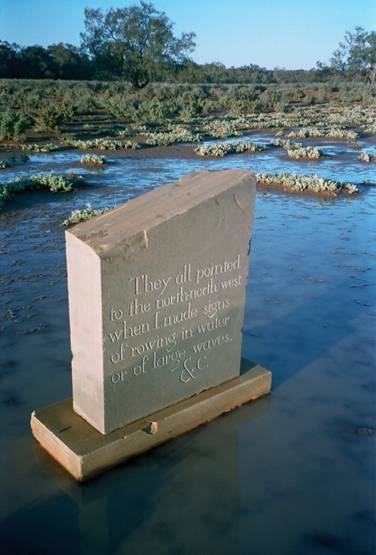

Figure 6. Signs of rowing, 2003, sandstone, collection Western Sculpture Park, Wilcannia

Mitchell was travelling down the eastern side of the Darling River in 1835, searching still for the inland sea. On the plain ahead, he saw three figures, Aboriginal men, their faces covered with red ochre, coming forward to meet him. He records that ‘They all pointed to the north-north-west when I made signs of rowing in water or of large waves and co.’ To their surprise, he gave them a greyhound pup, and moved on down the river. This happened at Paepipinbilla, now called Wilga, between Bourke and Wilcannia.

In 1844, north-west of Tibooburra, Sturt’s party saw three women in the far distance. As they approached, Sturt made a fire and boiled the billy. Their first meeting with Europeans was to sit down, have a cup of hot, sweet tea and a chat … some comfort in that, perhaps.

Carved text in stone can mark a place, communicate an event long gone, transmit the language of another time and place, or a drawing, take the printed word from a book in a library and establish it en plein air, educate, moralise, teach … it seems to me to be very versatile.

Inscription in stone has long been the prerogative of church and state. The inscription at the base of Trajan’s column was explicitly part of a tribute to a Roman war of conquest, but we all admire and respect the forms of the letters.

The Greeks would use inscription a little

differently. Diogenes, of Oananda (in modern

In our contemporary world, lettercutting is potentially at liberty to say anything at all: I think that this is partly why the form creates particular excitement among other artists. That liberty, though, requires focus.

Learning to draw and cut fine, classical letters in stone is a great pleasure and achievement. Having or finding something to say with that public language of stone is another matter, one where probably artisan and artist go their separate ways. The craft lettercutters in the British and Irish tradition have, mostly, worked to the specifications of their clients. Eric Gill did too, but broke through spectacularly to the high ground of his own visions, expressed in sculpture, and the high austere discipline of typeface design.

As I work, I often think of a couplet from the poet David Campbell:

Arm

your heart with the strict certainties of art

And turn your sorrow to

delight.

Ian Hamilton Finlay showed the way a more universal vision could be expressed in many media by delegation and commissioning. His devotion to a place is extraordinarily endearing: a secular consecration (perhaps not so secular). Endowing an unpromising bleak hillside with all the powers of Western mythology, personality and politics, and blurring the borders: garden and poem blur, symbol and metaphor, time, history. I am particularly fond, in a landscape artwork, of multiple resonance, where layers of meaning echo as a voice in a wooded valley.

Recently I have been drawing perimeter texts from Italian poets. I will read these to you in English, because, while I can carve Italian very well, I can’t speak Italian.

From St Francis of

Be

praised, my Lord, for sister water

Who is very useful and humble

and rare and chaste.

And from Petrarch (1304-1374):

From the lovely branches there came down (sweet in memory) a rain of flowers into her lap, and she sat modest amid so great glory, covered now by the loving shower.

It is pleasing to me that this text might be under a flowering tree or vine, perhaps a Robinia or wisteria, enacting each year in blossom the subject of the text. In this sense, the work ‘operates’ in a seasonal, devotional way in its setting long after we who make or commission it are gone. In this sense I want the works to look back to the classical past, and forward to the (classical?) future.

Petrarch is also the source for this inscription for a slate table, rich with the imagery of the ancient world:

From thought to thought, from mountain to mountain, Love leads me; since I find every marked path hostile to the life of quiet. If there is a stream or fountain on a lonely slope, if, between two hills, lies a shady vale, there the frightened soul calms itself.

Stone, of course, isn’t an immortal medium.

William Shenstone’s garden at the Leasowes, on which he spent, literally, a

fortune, is gone. Finlay has to wrap stone works in bubblewrap in winter to

save them from destruction by ice and frost. You know what happened to

But the Australian climate is kind to slate, at least to Australian slate. Mintaro slate memorials from the 1870s in the cemeteries at Wilcannia and Bourke suggest that my works will be burnished to the colour of a mulga brown snake and holding up well in 2140.

Figure 7. Headstone in Bourke cemetery, Mintaro slate

My works are really associated with all the pleasures that landscape and garden, books and pictures, can give to our minds and bodies. Stone, particularly slate, is a sensual medium, as is literature, as is landscape. What more could you wish for!